Forgotten, because once upon a time sanctity actually existed; because it was what inspired our civilization; because our people used to live among saints and they would draw from them the measure of their civilization; they were the heroes, the great champions, the “famous football players” and the “stars” of that time. Now, only the names of our saints remain, and even these have been “clipped” and altered in foreign fashion, while people now prefer to celebrate, instead of the memory of their saints, their personal birthdays. In times such as these, what can one say about sanctity? All words will fall on indifferent ears.

On the other hand however, how can one not speak of a matter so central and fundamental to a Christian’s life? Because without saints, our Faith is nonexistent; because if we leave out sanctity, there will be nothing left of the Church – only Her being identified with the world. Her “secularization” would be inevitable.

However, sanctity is not only “forgotten” in our day; it is also misinterpreted, whenever and however it is referred to. What is the significance of “sanctity”, when one sees it as a portrayal of the Kingdom of God, as an experience and a foretasting of End Times?

MISAPPREHENDED SANCTITY

Should someone randomly ask people on the street what, in their opinion, “sanctity” is about, the reply they will hear as a rule is the following: a saint is the one who does not sin, one who upholds God’s law, who is moral in every way – in short, someone sinless. Sometimes, an element of mysticism is added to the meaning of sanctity, according to which idea, a saint is one who possesses esoteric experiences, who communicates with the “divine”, who falls into a trance and sees things that other people don’t see – in other words, one who experiences supernatural situations and is able to perform supernatural acts.

In this way, the meaning of sanctity in people’s minds appears to be linked to moralistic and psychological criteria. The more virtuous one is, the holier he is. And the more charismatic a person is, displaying abilities that people usually do not have (such as reading others’ thoughts, foreseeing the future etc.), the more this induces us to regard him as a “saint”. The same applies reversely: when we discern a certain fault in someone’s character or behavior (such as gluttony, anger etc.), then we tend to write them off the “saint” list. Or, if someone does not display any supernatural abilities in one form or another, the thought alone that he could possibly be a saint, seems preposterous to us.

This common and widespread perception of sanctity gives rise to certain basic questions, when placed under the light of the Gospel, the Faith, and our Tradition. Let us mention some of them:

1. If sanctity is mainly about observing moral principles, then why was the Pharisee condemned by the Lord, whereas the tax-collector of the familiar parable vindicated? We usually call the Pharisee a “hypocrite”, but the fact is that he was not lying when he insisted that he faithfully upheld the Law, or that he gave 1/10th of his wealth to the poor, or that he did not omit to observe everything that the Lord demanded of him as a faithful Jew. He likewise was not lying when he characterized the tax-collector a sinner –as did the tax-collector himself- because the tax-collector was indeed unjust, and also a transgressor of moral rules.

2. A similar question also arises from the use of the word “saint” by the Apostle Paul in his Epistles. When addressing the Christians of Corinth, the Thessalonians, the Galatians etc., Paul calls them “saints”. However, further along in those Epistles, he points out the thousands of moral flaws of those Christians, which he censures most severely. In fact, in his Epistle to Galatians, it appears that the moral status of the “saints” there was so disappointing, that Paul was compelled to write to them that “if you bite and devour each other, take care that you do not exterminate each other!” So, how is it that the first Christians are referred to as “saints”, when it is certain that their daily life did not conform to the requirements of their very faith? I wonder, would anyone nowadays even consider calling any Christian a “saint”?

3. If sanctity is linked to supernatural charismas, then one would be able to seek it -and find it- outside the Church. It is a known fact that wicked spirits are equally capable of supernatural acts. Saints are not clairvoyants or fakirs, nor is their sanctity determined by such “charismas”. There are saints of our Church for whom there is no mention of miracles; while there have been miracle-workers who have never been recognized as saints. Quite interesting are –respectively- the words of the Apostle Paul in his 1st Epistle to the Corinthians, who, like many today, were impressed by supernatural acts: “…and if I have faith enough to move mountains, but have no love, then I am nothing…”. The Lord Himself had said that to command a mountain to move is possible, if you have faith “even as (small as) a mustard-seed”. But even this alone is not proof of sanctity; it is “nothing”, if the prerequisite of love does not exist – in other words, if it is something that any person without miraculous capabilities can have. Miracle-working and sanctity do not relate to each other, nor do they necessarily co-exist.

4. Similar questions also arise, when sanctity is linked to unusual and “mystic” psychological experiences. Many people revert to oriental religions in order to meet with transcendental “gurus” – men of exceptional self-discipline, ascesis and prayer; however, our Church does not regard them as saints, regardless how profound and supernatural their experiences may be, or how great their virtue may be.

Thus, the question is posed: do saints exist, outside the Church? If the word “saint” signifies that which people generally believe, as we described previously (that is, a moral lifestyle, supernatural charismas and supernatural experiences), then we will need to admit that “saints” do exist outside the Church (perhaps many more outside the Church, rather than inside it). If again we should wish to say that sanctity is possible only within the Church, then, we must seek the meaning of “sanctity” beyond the criteria that we mentioned previously – in other words, beyond moral perfection and supernatural powers and experiences.

So, let us see how our Church does perceive sanctity.

SANCTITY AS AN ECCLESIAL EXPERIENCE

The term “saint” has an interesting history. The root of this Hellenic word – (h)ágios – is in the fragment “ag”, from which a entire series of terms are produced, such as “agnós” (=pure), “ágos” (=with positive inference, an object of religious reverence; with negative inference, a miasma, or curse). The deeper significance of this root is found in the verb “άζεσθαι” (pron.: á-zes-thae), which means to be in awe of a mystical and tremendous power (Aeschylus); also, the respect afforded to the bearer of Power (Homer, Odyssey 9200 e.a.) etc.. Thus, in ancient Hellenism sanctity was linked to power; to that which Otto had called “mysterium fascinosum et tremendum” – that which simultaneously inspired attraction and fear.

In the Old Testament, the Semitic word which was translated (into Greek) by the Septuagint Fathers as “saint” (hágios) is the word godes, which is closely related to the Assyrian word kuddushu, which means “to sever, to separate, to discern radically, to cleanse” (hence its linkage to cleanliness and chastity). Saintly things are those that are discerned from among the rest – mainly in worship – and are dedicated to God.

Thus, the Holy Bible goes beyond the psychological significance that we observe in the ancient Hellenes (awe, fear, respect towards a superior power) and it links the notion of “saint” to an absolute otherness, to the absolute Other – something that eventually leads the Holy Bible to link the term “saintly” (=holy) to God Himself – that is, to an absolute transcendence – when relating it to the world. Only God is “saintly” (holy), and therefore every sanctity springs from Him and from a relationship with Him.

In order to emphatically stress this belief, in the Old Testament Isaiah (the prophet of God’s holiness) calls upon God three times: “Holy, holy, holy, the Lord Shabuoth”, which in the Hebrew form of triple repetition signifies “infinitely holy” (compare to the 777 and its opposite, the 666, for which so much fuss and fear abounds nowadays).

Consequently, for the Holy Bible “sanctity” relates to God and not to any person or sacred article, as in ancient Hellenism; it becomes a persona, and in fact, with the Fathers of the Church it is linked to the Holy Trinity, with which the Fathers have related the Prophet Isaiah’s “thrice-holy”. For the Christian faith, sanctity (holiness) is therefore not man-centered, but God-centered and is not dependent on the moral achievements of Man -great though they may be- but on the glory and the grace of God and the degree of our personal relationship with the personal God. It is for this reason that the Holy Mother, the Theotokos is named “Pan-agia” (all-saintly) or “Yper-agia” (supremely saintly): not on account of Her virtues, but because more than any other person in History, She alone became personally united with the most holy God, by providing flesh and blood to the Son of God.

For the Church, therefore, sanctity is not the personal property of any one person, no matter how “saintly” one may be in their lifetime; it has to do with one’s personal relationship with God. God, according to His own free will, sanctifies whomever He chooses, without sanctity being dependent on anything else, other than the free will of the one being sanctified. As stressed by saint Maximus the Confessor, we people do not contribute anything, except only our willingness, without which God will not act; furthermore, our labours and ascesis do not produce sanctity as a result thereof, as they can be proven to be worthless chaff.

In the Christian faith, this relating of sanctity to God Himself leads to its linking to the very glory of God. Sanctity-holiness now means the glorification of God by the entire world. It is not perchance that the primary request in the Lord’s Prayer is: “hallowed be Thy Name”. If we stop to consider that this prayer is eschatological –that is, it refers to the final state of the world- it is obvious that what we ask for in the Lord’s Prayer is for God to be glorified by all the world; for the moment to come when all the world will cry out together with the Cherubim what Isaiah had seen and heard in his vision: “Holy, holy, holy is the Lord Shabaoth; replete are the heavens and the earth with Your glory! Hosanna, to the One on high!”

The saints do not seek any personal glory, but the glory of God. God glorifies the saints, not with their own glory, but with His glory. The saints are sanctified and glorified, not with a sanctity and a glory that springs from within them, but with the sanctity and the glory of God Himself (notice how Byzantine iconography depicts the light as being directed externally, onto and into the subjects portrayed). This is of special significance for the theosis of the saints.

As elucidated during the hesychast arguments of the 14th century and contrary to western theology which spoke of “created” grace (i.e., that grace and glory belong to the very nature of Man, as supposedly given by God during Creation), Orthodox theology –as developed by saint Gregory Palamas and the other hesychasts of that era– perceives the light that the saints see, as well as the glory that envelops them, as the “uncreated” energies of God; that is, as the light and the glory of God Himself. A true saint is the one who does not seek personal glory in any way, but only the glory of God. When one seeks personal glory he loses his sanctity, because in the long run, none other is holy except God. Sanctity-holiness involves a partaking and communing of God’s holiness; after all, that is what “theosis” (deification) means. Any sanctity that hinges on our virtues, our morality, our qualifications, our ascetic labors etc. is demonic, and has nothing to do with the sanctity of our Church. From these observations, it becomes obvious that the par excellence source of sanctity-holiness is found in the Divine Eucharist. Let us elaborate somewhat on this position.

We have said that there is no other sanctity-holiness other than that of God, and that the saints do not possess any sanctity of their own, but partake of God’s sanctity-holiness. This means that in the Church, we do not have saints, except only in the sense of those who have been sanctified.

When, during the 4th century A.D., discussions were taking place on the subject of the divinity of the Holy Spirit, the main argument presented by saint Athanasius to prove that the Holy Spirit is God and not a creation, was that the Holy Spirit cannot be sanctified, instead, It sanctifies. If the Holy Spirit could be sanctified, then It would indeed be a creation, because creations –and consequently humans- do not sanctify; they are sanctified.

In His Magisterial prayer, as preserved in John’s Gospel and cited in the first of the “twelve gospel readings” of Easter Thursday, Christ utters this meaningful phrase to the Father: “…for their sake(=the disciples, and by extension, all people) do I sanctify Myself, so that they too may in truth be sanctified…”. These words were spoken just prior to the Passion, and, when related to the Last Supper, they acquire a Eucharist meaning: with His sacrifice, Christ Himself (as God) sanctifies Himself (as a human), so that we humans may be sanctified through Communion of His Body and His Blood. With our participation in the Divine Eucharist, we are sanctified; that is, we become saints by partaking of the one and only Holy (“saintly”) One: Christ.

Perhaps in a Christian’s life there is no point as revealing (as to what sanctity is), than the moment when the priest raises up the Precious Body prior to Holy Communion, saying: “the sanctified (the holy Body) unto the sanctified (the saints)” – in other words, the sanctified (holy) Body of Christ and His Blood are now being offered to the sanctified ones (the “saints”), the members of the Church, for communion. The response of the laity following these words is overwhelming (inasmuch as it summarizes everything that we said previously): “One (only) is Holy, One is the Lord: Jesus Christ, in glorification of God the Father”. Only one is actually holy: Jesus Christ. We all are sinners. And His sanctity-holiness does not aspire to anything else except the glorification of God (“in glorification of God the Father…”). It is at that precise moment that the Church experiences sanctity-holiness at its apex. By confessing that “One is Holy”, every single virtue of ours and every worth vanish before the sanctity-holiness of the Only Holy One. This does not mean that we can approach Holy Communion without any prior preparation and labour for a worthy approach. It does however imply that no matter how much we may prepare ourselves, we do not become saints before having received Communion. Sanctity does not precede the Eucharist communion; it follows it. If we are saints prior to receiving Holy Communion, then what is the purpose of Holy Communion? Only our participation in the sanctity-holiness of our God sanctifies us, and that is what Holy Communion offers us.

From this observation springs a series of truths that are relevant to our subject:

The first one is that in this way, we can comprehend why –as mentioned earlier along in our homily- in the Epistles of the Apostle Paul all the members of the Church are referred to as “saints”, despite the fact that they were not characterized by moral perfection. Given that “sanctity” –as regards the people– connotes a partaking of God’s sanctity-holiness in the manner that it is offered by Christ, Who sanctifies Himself with His Sacrifice, then all the members of the Church who participate in that sanctification can be called “saints”.

By the same token, ever since the first centuries in the Church, all the elements of the Eucharist had also acquired the name “holies” (the “sanctified”, as above: “the sanctified unto the sanctified”), even though by nature they are not holy. And it is for the same reason that the Church had bestowed at an early stage the title of “saint” to the Bishops. May people are scandalized nowadays when we say “the saint (such and such)”. For example, a certain reporter whose main job was to project the scandals of bishops, had intentionally printed the word ‘saint’ placed inside quotation marks, before the bishop’s name. Bishop are addressed in this manner, not as an indication of their virtues, but because in the Divine Eucharist it is they who portray the Only Holy One; they are the ones who are images of Christ, who are standing in the place and the in manner of God, according to Saint Ignatius. It is the place of the Bishop in the Divine Eucharist that justifies the title of “saint”. Before undergoing the corruption of pietism, the Orthodox had no difficulty whatsoever with the terminology of portrayals, and would “see” Christ Himself in the person of the one who was portraying Him during the Divine Liturgy, that is: the bishop.

Thus, the Divine Eucharist is the par excellence “communion of saints”. That is what the labours of the ascetics aspire to, which labours are never the end, but only the means towards the end, which is the Eucharist communion. This point is forgotten and overlooked by many contemporary theologians, even Orthodox ones, who especially in our day tend to relate sanctity to ascetic labours.

The case of saint Maria the Egyptian is an eloquent example. For forty entire years, she laboured ascetically in the desert with all her might in order to be cleansed of her former passions/sins, but it was only when she received the communion of the Immaculate Gifts from the saint did her earthly life come to an end, having then become sanctified. The aim of her ascesis was the Eucharist communion. Would Maria have been a saint, if she had been cleansed of passions, but had not received Holy Communion? The answer is most probably no.

However, the Divine Eucharist is the culmination of sanctification, not only because it offers Man the most perfect and fullest union (physical and spiritual) with the Only Holy One, but also because it comprises the most perfect portrayal of the Kingdom of God; that is, the state in which all of Creation will be eternally and incessantly sanctifying and glorifying the “holy, holy, holy Lord Shabuoth”.

From the book «Sanctity, a forgotten vision», Akritas publications.

Source: Periodical “PIRAIKI ECCLESIA”, No. 187 – November 2007 – p. 2-7.

Re-published by the blog: Manitaritoubounou

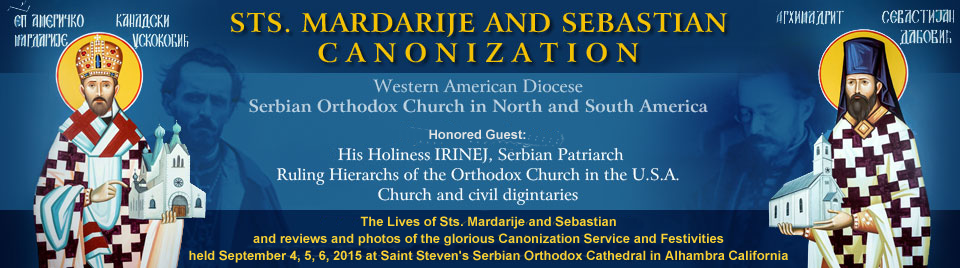

This DVD is an historical video presentation on the life and work of Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovic, a man referred to by St. Nicholai (Velimirovic) of Zhicha, Serbia, as “the greatest Serbian Missionar of modern times.”

This DVD is an historical video presentation on the life and work of Archimandrite Sebastian Dabovic, a man referred to by St. Nicholai (Velimirovic) of Zhicha, Serbia, as “the greatest Serbian Missionar of modern times.”